Surgery is the last thing that anyone wants for a Crohn’s patient, but it is often the course of last resort. When that happens, it can be beneficial to know what types of surgeries are most often performed, and why.

Typically, the surgeries required for Crohn’s disease fall into one of four categories. They are:

- Partial bowel resection (removal of a part of the intestines)

- Strictureplasty

- Correcting fistulas

- Draining an abscess

Bowel Resection

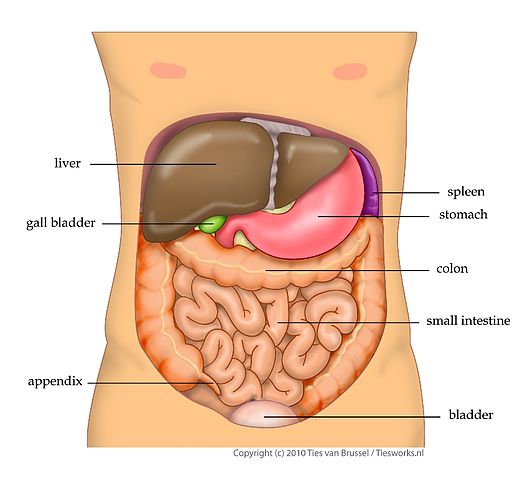

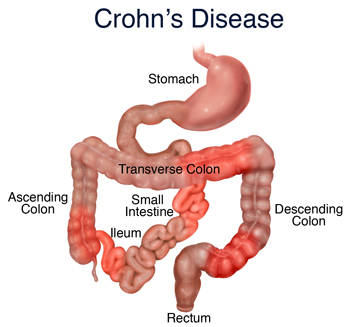

Unlike many types of IBD, in Crohn’s patients there can be found long lengths of healthy bowels intersected by portions of severely diseased tissue. The terminal ileum, the ileocecal valve, and a small portion of the large intestine tend to be the most common areas for the diseased tissue to be found.

Once the tissue is so diseased that it causes an obstruction or partial obstruction that can’t be relieved through the use of medications, surgery must be performed to correct the situation.

Most often, the doctor will cut out the diseased portion of the intestines and rejoin, or anastomose, the healthy ends of the remaining bowels. If there is too much inflammation for this to be done at the time of the surgery, the doctor may perform an ostomy – draining the waste directly out of the body into a plastic bag through a hole in the abdomen – until six to eight weeks after the surgery. This allows the intestines time to shrink.

The doctor will then open the patient back up to join the portions of the intestines and close the ostomy site on the body.

Strictureplasty

This type of surgery is performed to help alleviate areas of the intestines that have narrowed to the point of causing an obstruction.

In this case, a small incision is made in the intestine along the length of the bowel where the stricture is. This incision is then pinched closed against itself the short way and sewn closed. While it shortens the portion of the intestines, it widens the area that was formerly to narrow to allow the passage of waste.

Correcting Fistulas

A fistula is a canal joining the intestines with either another portion of the intestines or another organ of the body. These are caused by ulcers eating through the bowel and whatever the bowel was resting against. When the sore begins to heal, it grows tissue around the areas, linking them together, and usually allowing the waste of the intestines to drain into the other organ.

In order to correct this, a surgeon must enter the abdominal cavity and cut the intestine away from the other organ. He or she must then close the two holes to avoid further crossover before closing the patient back up.

Draining an Abscess

A pus-filled abscess in the body cavity is not only painful, but it’s dangerous. Filled with a concentrated infection that cannot be touched by antibiotics, the abscess has to be drained in order to heal. If the blister should burst before it can be drained, the infection will seep into the surrounding areas with the potential of causing such a severe infection that it could cause death.

Because of this, the abscess must be drained as soon as possible. Depending on where the abscess is, this can be done via a laparoscopy or during an open abdominal surgery. Either way, the intent is to lance, or cut, the blister and drain the fluid. If this can be done quickly during the surgery, the surgeon will mop up the fluid, clean the area thoroughly, and then close the patient.

Sometimes, however, this isn’t so easily done. Abscesses may continue to drain long after the surgeon has changed out of his scrubs and hit the back nine.

To avoid this drainage from infecting the entire body cavity, a catheter, or tube, will be sewn into the tissue of the blister and then secured to the abdomen through a tiny incision. The abscess will then be able to drain the fluid to the outside of the body. Once the draining ends, the doctor will remove the catheter and close the incision in the abdomen.